“To be surprised, to wonder, is to begin to understand.”

Jose Ortega Y Gasset (1930)

Jhetovi Gease of Warrenton is the curious type. In the electron microscopy course he is taking this spring at Catawba College with Biology Professor Dr. Steve Coggin, Jhetovi has gathered all kinds of biological specimens to examine very closely. And, the digital portfolio he’s created of his work with the microscope would make even the most discerning modern artist quite envious.

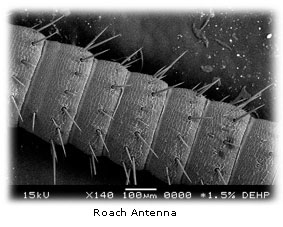

Although Jhetovi’s images look like the stuff that dreams or even nightmares are made of, they are actual black and white photographs of real-life specimens taken at great magnification. There’s his fly eye, and the mouth of a worm, the eight eyes of a spider, the spider’s fang, and the antenna of a roach. Each is a quite beautiful documentation of microscopic perfection -- that is unless you stop to think about what you’re actually seeing. Then, the names of the specimens don’t exactly reinforce their digital beauty, but rather conjure images of a potent witches’ brew.

;

;

Jhetovi smiles as he holds up a small container with two roaches running around inside it. Parts of these insects will soon be examined in great detail under the electron microscope. “Somebody at work gave these to me,” he explains. “She found them out back and asked if I wanted them and of course, I said, ‘Yes.’ ”

Jhetovi and his five classmates are pioneers of sorts since their work in Coggin’s class is the first to be performed on two of Catawba’s new electron microscopes. The $60,000 scanning electron microscope is the piece of equipment which allows the students to take digital images of the surface features of their biological specimens. In another lab nearby, a new transmission electron microscope allows the students to examine the cellular makeup of a specimen. The two instruments are complimentary with the scanning electron microscope examining the surface and the transmission electron microscope looking at internal detail at high magnification.

According to Coggin, students who work with these two new microscopes will have a wealth of marketable skills to use in the workplace after their college graduation or to use in graduate school if they opt to continue their education. “This is a highly specialized course that they’ll be able to put on their resumes. They’ll each have new skills that they’ll be able to use,” Coggin explains, noting that hospitals, research institutions and many businesses which need a high degree of quality control in their manufacturing processes, such as microchip producers in the computer industry, have similar equipment.

The scanning electron microscope employs a 15,000 volt electron gun that shoots an electron beam onto a specimen which is suspended in a vacuum chamber. Those scattered electrons create the black and white images seen by the students on the computer screen. The students can manipulate the microscope and therefore, the image they’re seeing, using focus, contrast or stigmatism controls to produce very exacting digital photographs. These photographic images are black and white because no light waves are involved in the imaging process.

Course requirements specify that each student must submit a portfolio of five different images of three biological specimens along with a caption for each which details what part of a specimen is pictured at what magnification, along with the genus and the species names for that specimen.

Hollie Bruce of Salisbury chose to examine part of the furry underside of a magnolia leaf and a green pepper seed with the microscope. Hollie admits she took a look at a piece of chalk under the microscope “before I realized we were supposed to look at biological samples, only.” She was able to see the air pockets within the chalk.

Ashley Wilhelm of Cleveland got a close-up look at a hair from her head and the downy feather of a chickadee. She seemed a little dismayed that the chickadee feather yielded the more picturesque image. “That’s my hair and I hope it’s supposed to actually look like it does,” she says. “That’s why you don’t want to take a picture of anything from your own body, in case it looks weird,” laughing as she recalled her examination of one of her fingernails under the electron microscope.

Mandy Durham of Salisbury examined a hair from her head and was a bit alarmed when she saw extra strands of something apparently wrapped around that hair. Dr. Coggin contends it was likely conditioner or a hair gel build-up that Mandy was seeing in that particular photograph.

And the students, Coggin says, have inspired each other with their close-up image capturing. “I was going to look at the skin of a kiwi, but Jhetovi said it wasn’t that cool,” notes Andrew Frank of Salisbury. Instead, Andrew took another cue from Jhetovi and his digital image of a fly eye and decided to examine a mosquito eye with good success.

“The electron microscopes have expanded the way our students view the world. They are a new way of seeing that has compelled the students in the class to examine the world more closely,” Coggin concludes.